TLDR

Since late 2024, Serbian students and citizens have led mass protests sparked by the Novi Sad station collapse and fueled by years of corruption, media control, and democratic backsliding under Aleksandar Vučić, demanding accountability, free elections, and rule of law.

What Is Going On In Serbia?

Serbs have made international headlines due to their battle for democracy. But like an iceberg, there's much, much more to this story than first meets the eye.

Table of contents

Introduction: Vučić’s Rule and Public Discontent

President Aleksandar Vučić has dominated Serbian politics for over a decade, consolidating power through a series of electoral victories and controversial governance practices.

Who Is Vučić?

Aleksandar Vučić is Serbia’s dominant politician of the past decade.He co-founded the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) in 2008 after breaking with the ultranationalist Serbian Radical Party ↗, became prime minister in 2014, and has served as president since 2017.He presents himself as a pragmatic leader who wants EU membership while maintaining close ties with Russia and China.Critics describe his rule as increasingly authoritarian, marked by pressure on media and institutions.

His 1990s Roots Under Milošević

Despite Vučić's modern rebranding in the 00s and beyond, he began his career as an ultranationalist, actively aiding in war efforts during the Balkan wars in the 90s.This is how the timeline of his political career looks.

Coalition with Milošević. Vučić rose in the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), which joined a governing coalition with Milošević’s Socialists (SPS) and the Yugoslav Left in March 1998. That coalition governed Serbia through the Kosovo war and NATO bombing.

Minister of Information, 1998–2000. At age 28 he became information minister in the Mirko Marjanović government. Under his watch, Serbia enacted a draconian Public Information Law that imposed heavy, 24-hour-payable fines, enabled property seizures, and was used to shut or cripple independent outlets such as Danas and Dnevni Telegraf. Human Rights Watch and the Committee to Protect Journalists documented the law’s use during wartime censorship.

Overthrow of Milošević. Student-led and civic protests culminated in the 5 October 2000 “Bulldozer Revolution,” which brought down Milošević and ended Vučić’s tenure as minister.

Rebranding after 2008. Vučić left the SRS in 2008 to help found the SNS, adopted more pro-EU rhetoric, and has said he “made mistakes” in the late 1990s. Reuters profiled this shift when he returned to power.

Here's the infamous video from his career as a Minister of Information, where Vučić proudly announced:"For every Serb, we will murder 100 Muslims, and we will see what the international community will do about it... they cannot mess with the Serbian people".

Why Organized-Crime allegations Follow Him

The allegations link parts of Serbia’s “hooligan” scene and crime networks to politics and security services.Here are the strands you will see most often.

The Belivuk case and hooligan networks. Police arrested Veljko Belivuk, a Partizan ultras leader, in 2021. At his 2022 trial, Belivuk claimed his group had “served the needs of the state” ↗ and alleged contact with top officials. Vučić publicly rejected those claims. RFE/RL and BIRN documented both the arrests and the courtroom accusations.

Media smear campaigns vs. investigative outlets. Serbia’s pro-government tabloids attacked investigative newsrooms like KRIK following their investigations linking upper echelon politicians with crime gangs. OCCRP ↗ and Balkan Insight ↗ reported on those smear campaigns and the pressure on independent reporters covering crime-politics overlaps.

Photos of Vučić’s son with crime suspects. KRIK and OCCRP published photos ↗ showing Vučić’s son Danilo in the company of Aleksandar “Aca Rošavi” Vidojević, a hooligan figure linked by media to the Kavač clan.

International and local reporting on alleged ties. U.S. and European outlets have repeatedly published investigations into Serbia's President. Here are a few: The New York Times ↗, KRIK ↗, Le Monde ↗, Gazeta Express ↗ .

Vučić’s Rise to Power

Vučić’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) first entered government in 2012, and he became prime minister in 2014 after a landslide win. In 2017, Vučić won the presidency amid accusations of media bias and fraud.Vučić's election prompted spontaneous student-led protests under the slogan “Against Dictatorship” ("Bez diktature"). Those 2017 protests fizzled without concessions, but they marked the start of mounting civic resistance to Vučić’s increasingly authoritarian actions.

Democracy Erodes

Since 2014, Serbia’s democracy has eroded significantly.Independent watchdogs note that Serbia slipped from a fledgling democracy into “electoral autocracy,” with one of Europe’s sharpest declines in freedom and institutional checks and balances.Vučić’s SNS-led government has tightened its grip on media, weakened independent institutions, and faced allegations of corruption and links to organized crime.Critics have even labeled Serbia under Vučić a “mafia state” due to extensive state connections with criminal networks. Vučić rejects such claims, but widespread public frustration has grown over corruption, patronage, and democratic backsliding.

Unfair Elections

Major elections during Vučić’s tenure have often been marred by controversy.The SNS won early parliamentary polls in 2016 and again in 2020 (the latter amid an opposition boycott), giving Vučić near-total control of parliament. Vučić himself was re-elected president in 2022.Opposition and international observers frequently criticize the unfair conditions under which elections are held. For example, snap parliamentary elections in December 2023 were conducted under unjust conditions, according to European monitors, and the opposition rejected the results as fraudulent. This led to post-election protests in late 2023, which security forces dispersed by force.Each disputed election and crackdown further fueled public discontent, setting the stage for the larger upheavals to come.

Previous Waves of Civic and Student Protests under Vučić

Popular discontent with Vučić’s rule has periodically erupted in mass protests over the years.Below are some of the biggest protest waves.

2015–2017: “Don’t Let Belgrade D(r)own” and Savamala

“Don’t Let Belgrade D(r)own” (Ne da(vi)mo Beograd) began as a civic movement against the Belgrade Waterfront megaproject ↗ on the Sava riverfront. Many people from Belgrade opposed the project. Activists criticized the opaque contract and alarming urban planning shortcuts.Despite widespread public opposition, and some people still living in the district, in April 2016, at 4am in the morning, around 30 masked men illegally demolished buildings in Belgrade’s Savamala district. Police failed to respond to repeated calls. Serbia’s Ombudsman reported deliberate police non-response. Weeks later, then-Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić said “top city officials” ordered the action, which protesters saw as proof of state capture.Don't Let Belgrade D(r)own organized a series of large marches in 2016–2017, drawing thousands in central Belgrade with “Whose city?” and “We want accountability” as core messages. Demonstrators demanded resignations of named city and police officials and a transparent probe.Eventually, the representatives ran for Belgrade city assembly in 2018, then entered the national parliament in 2022 as part of the green-left coalition “Moramo”, securing five MP slots.

2017: “Against Dictatorship”

After Vučić’s April 2017 presidential victory, thousands of mostly young Serbians took to the streets in Belgrade and other cities, decrying the election as fraudulent.These leaderless rallies, organized via Facebook, were the first major challenge to Vučić’s rule.Though they eventually died down without major concessions, they signaled youth frustration with perceived authoritarianism.

2018–2020: “1 Out of 5 Million”

In late 2018, the brutal assault of an opposition politician sparked a massive movement.Demonstrators adopted the slogan “One Out of Five Million” (#1od5miliona) after Vučić declared he wouldn’t give in “even if 5 million people” protested.Starting in winter 2018–2019, tens of thousands marched weekly in Belgrade and other cities, demanding free media, fair elections, and an end to violence against government critics.

These rallies, which are among Europe’s longest-running at nearly 15 months, shook the regime.Vučić sought to defuse them by mobilizing pro-government counter-rallies and agreeing to a mediated dialogue on electoral reforms.The movement lost momentum by mid-2020, amid the opposition’s election boycott and a COVID-19 ban on gatherings.

2021–2022: Environmental Protests

Outside the politically-motivated gatherings, Serbia saw mass ecological protests in late 2021.Anger over a proposed lithium mine project by Rio Tinto ↗ and laws seen as favoring big investors led to tens of thousands blocking highways and bridges across the country.The public outcry forced the government to suspend the mining project and withdraw controversial laws by early 2022.These protests, though short-lived, showed the ability of civil society to win concessions on non-partisan issues (in this case, environmental protection).

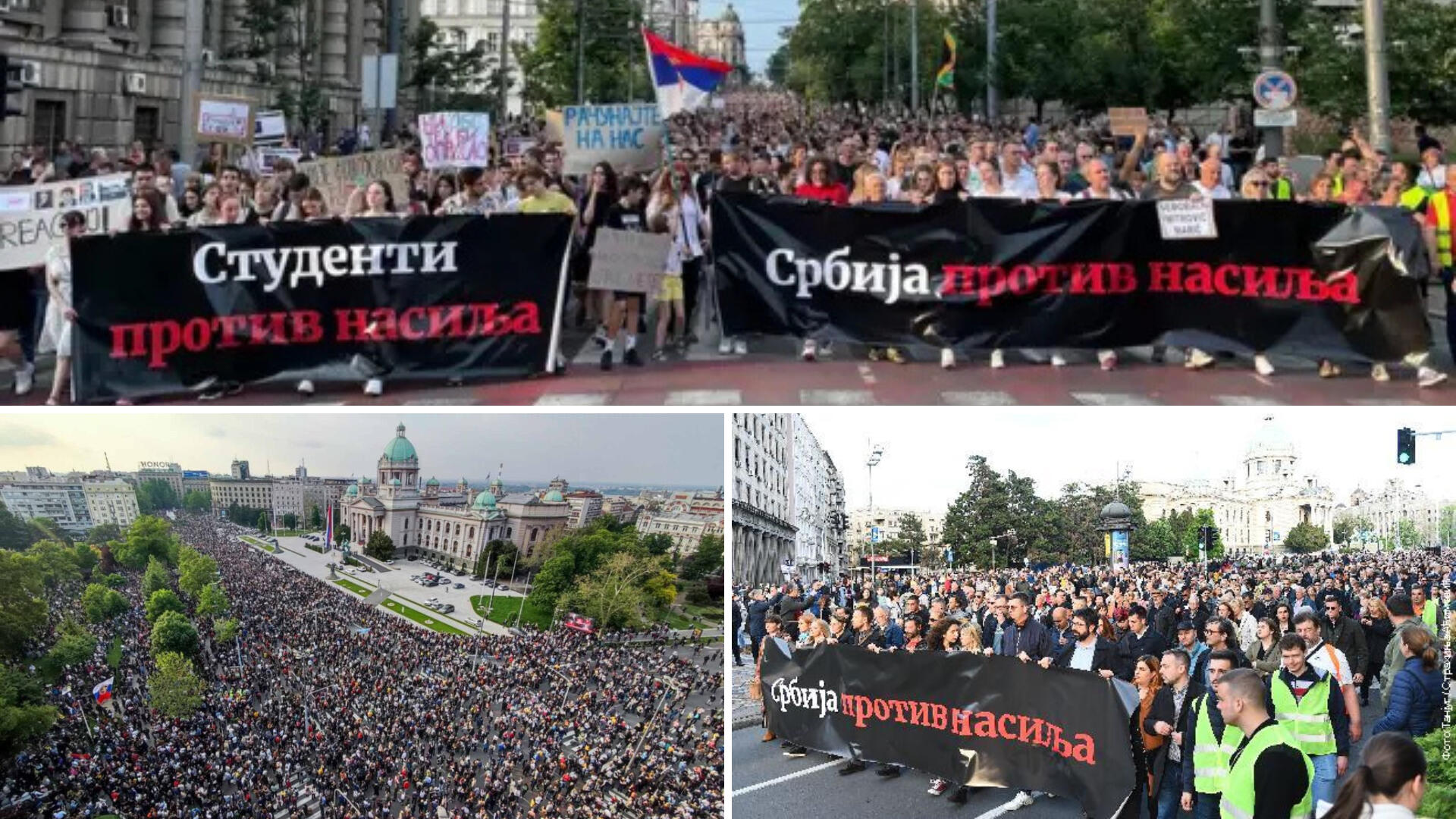

2023: “Serbia Against Violence”

In May 2023, Serbia was shaken by two back-to-back school shootings ↗, which left 17 people dead. Shock quickly turned to outrage at what protesters called a “culture of violence” fostered by the government and its media.In response, crowds of tens of thousands marched under the banner “Serbia Against Violence” (Srbija protiv nasilja). They demanded the resignations of top security officials (the interior minister and intelligence chief) and the shutdown of pro-government TV stations accused of promoting violence and crime.Vučić’s government yielded on paper (the police minister was replaced and some reality TV programs were canceled), but he also organized a massive counter-rally of supporters and resisted deeper changes. This approach is Vučić’s modus operandi for suppressing dissent.Eventually, Vučić agreed to hold early parliamentary elections in December 2023, hoping to reset the situation. When those elections occurred under dubious conditions and the ruling party prevailed, the “Serbia Against Violence” movement denounced the results as stolen and staged new protests.Those late-2023 protests were met with riot police and fizzled under pressure, but public resentment only grew.

A Nation at a Breaking Point

Through each of these episodes of protests, more and more Serbs grew increasingly frustrated with Vučić.But a big cloud of doubt was still in the air. Vučić's ties to crime gangs and history of violence made many fearful for their lives, or the lives of their loved ones.Furthermore, with protest after protests ultimately failing to make significant political improvements, the nation was exhausted, and many eventually gave up on ever seeing things change.By late 2024, Serbia was, in effect, a nation on edge, waiting for the next catalyst to voice its grievances.

What the 2024/2025 Protests Mean In the Grand Scheme of Things

The political, economic and social tapestry behind 2024/25 protests in Serbia is complex.What started as an outcry over a fatal accident morphed into a broad movement demanding justice and government accountability.Ultimately, the protests reached a fever pitch in violent clashes in the summer of 2025.

The Cause and the Catalysts

The immediate cause of the 2024–2025 protests was the Novi Sad station tragedy ↗, but the movement’s energy comes from deeper grievances.Years of perceived corruption, cronyism, and erosion of rule of law created a powder keg environment. The fact that a newly renovated public project (celebrated by authorities as a success) could collapse and kill citizens was a direct manifestation of high-level corruption and incompetence.

Students and activists adopted the slogan “Corruption Kills” (Korupcija ubija) and “Your hands are bloody” (Ruke su van krvave) arguing that government graft and negligence were literally endangering and ending lives.Many Serbs, especially the youth (dubbed “generation Vučić” as they grew up under his rule) are fed up with limited economic opportunities, partisan patronage, and stifling of dissent. Many have seen their parents and older relatives protest for democracy in the streets. Others left the country in droves ↗ in pursuit of a better future.The slogan “Serbia Without Violence” from 2023 evolved into a broader demand to stop state-fueled social and institutional collapse.In short, the station collapse lit the fuse, but public outrage over systemic issues provided the explosive force behind the sustained protests ↗.

Student Demands

The protest was started by students who wanted justice for the railway tragedy.From the beginning, they articulated clear demands ↗.These include:

Publication of the complete documentation concerning the reconstruction of the Novi Sad Railway Station, which is currently inaccessible to the public.

Confirmation from the relevant authorities of the identity of all persons for whom there is reasonable suspicion that they physically assaulted students and professors, and also the initiation of criminal proceedings against them. Furthermore, the dismissal of these persons is demanded, if it is shown that they hold public office.

The withdrawal of criminal charges against arrested and detained students during the protests, as well as the suspension of already initiated criminal proceedings.

An increase of 20% in the funding allocated to state universities.

By early 2025, the student protests and demands spread nationwide.The call for Vučić and his SNS to relinquish power at the ballot box became a central rallying cry of the nation.Demonstrators believe only a fair election can “restart” Serbia’s democracy and remove what they see as an entrenched corrupt elite.

Timeline of the 2024-2025 Protests

November 1, 2024: Novi Sad Station Collapse

A deadly disaster struck Novi Sad (Serbia’s second-largest city) when the 48m-long concrete canopy of a railway station collapsed onto people walking and sitting underneath, killing 16 people and severely injuring one.The station had just been renovated and reopened a few months earlier as part of a high-profile modernization project funded by China’s Belt and Road Initiative.Public shock quickly turned to anger as evidence emerged suggesting that the canopy was over 23 tons heavier than originally designed ↗ and that crucial safety checks were skipped ↗.The roof collapse became a galvanizing symbol of government incompetence and corruption, sparking immediate calls for accountability.

Early November 2024: Outrage and Initial Protests

Within days of the Novi Sad tragedy, students organized, demanding justice.On November 3, protesters gathered outside the Ministry of Construction and Transport in Belgrade, demanding the resignation and arrest of any officials responsible.The government launched an investigation and theThese moves, however, did not quell public anger, as protesters believed these were nothing more than performative actions, without real political bite.Vigils and rallies continued in Novi Sad and Belgrade, with demonstrators carrying pictures of the victims and signs reading “Corruption Kills”.

Mid-Late November 2024: Protests Spread and Intensify

University students in Novi Sad took the lead, organizing daily marches ↗.On November 6, a large protest at the Novi Sad station turned chaotic when some protesters clashed with police; officers used tear gas, and at least 12 people were injured in the fray.Over the next days, the unrest spread to other cities. By mid-November, thousands were rallying in Belgrade, Niš, Kragujevac, and beyond.Demonstrations remained peaceful but emotionally charged: protesters in Novi Sad held a silent vigil, blocking major crossroads in complete silence to honor the (at that point) 15 lives lost.By this time, media censorship and broader corruption had become core themes alongside the disaster itself. Crowds chanted against Vučić and SNS, blaming top leaders for creating a system where tragedies happen “because of theft and incompetence.”The slogan “He is finished!” (aimed at Vučić) began to echo in the streets.

December 2024: Vučić’s Partial Concessions

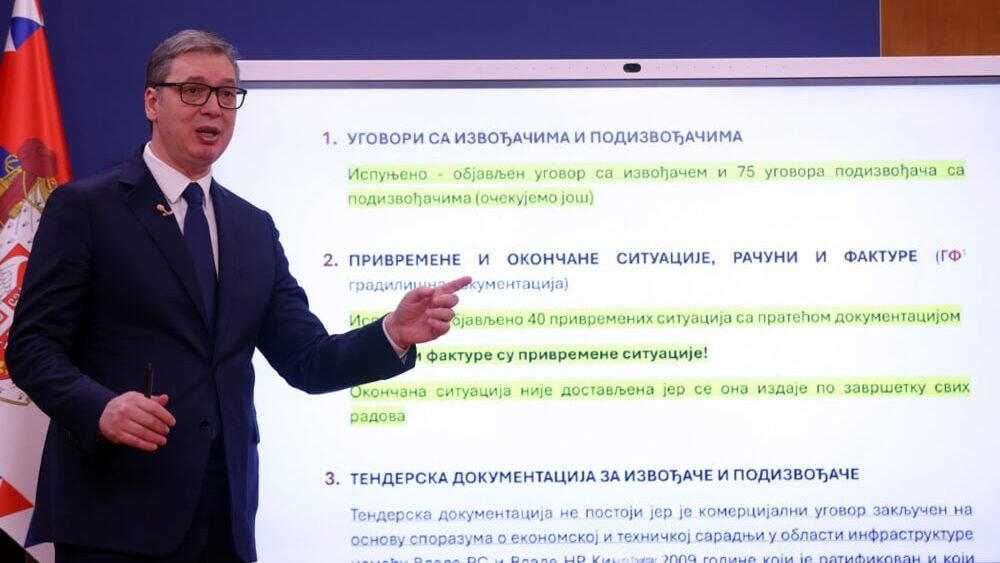

Vučić felt growing pressure nationally and internationally.On December 11, he held a press conference and promised to fulfill several of the students’ demands ↗.

However, Vučić refused to step down or call new national elections – two key demands of many protesters.By mid-December, indictments had been filed ↗ against 13 individuals for a serious offense against public safety, including the Minister of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure Goran Vesić.It was apparent that the government hoped that scapegoating a few officials and offering (performative) transparency would defuse the movement. It didn't work. ↗ The core of the protest movement persisted, skeptical of cosmetic fixes and still pressing for deeper change.Grasping at straws, Vučić organized a hostile campaign and a threat of violence on a group of international students from Croatia ↗ who were visiting Serbia. Upon their arrival at their hotel in Serbia, they were asked for ID and photographed. Then they were told to "never show up in one of the student protests, or you'll never be allowed in Serbia again". Then, at the border cross back to Croatia, Serbian border police gave the students a box full of plums (symbolizing blue eyes from being punched) and a message from the secret service of Serbia. Furthermore, the government publicly showed the young people's faces, names and addresses while calling them "enemies of the state" and "foreign spies".

January 2025: Escalation and Government Shake-up

After a brief holiday lull, protests regained momentum in January.Tensions spiked on January 27, 2025, when a group of masked thugs armed with baseball bats attacked student protesters ↗ occupying a building at the University of Novi Sad. Several students were beaten – one young woman was seriously injured – in what protesters believed was an act of intimidation by government-linked hooligans.

The incident outraged the public. The very next day, January 28, crowds in Novi Sad and Belgrade swelled again, with students painting red “blood” on their hands to protest the violence.In an attempt to calm the crisis, Prime Minister Miloš Vučević resigned on January 28. Vučević – a close Vučić ally and former Novi Sad mayor – announced he was stepping down “to preserve peace,” effectively sacrificing himself as a political concession. (Notably, Parliament delayed formally accepting his resignation until March, illustrating the regime’s reluctance to relinquish control.)Vučević’s resignation was the most significant political fallout on paper, but it was nothing more than yet another scapegoat ↗, as Vučić is the only person in Serbia's government with real power.

February–March 2025: The Movement Expands and Organizes; International Support Grows

Through late winter, demonstrations continued daily across Serbia.Students solidified their leadership of the movement via groups like “Students Against Authoritarian Rule” and an informal network called “Students in Blockade.” University faculties and even high school students joined in acts of civil disobedience.By mid-March, protesters were marching and blocking traffic for 15 minutes every day at 11:52 a.m.

Entire university campuses were occupied by students, effectively shutting down classes in all state universities.Many secondary schools went on strike as teachers and pupils voiced support. This was a rare occurrence in Serbian history – a nationwide youth-led protest that had broad backing from older generations, labor unions, professionals, and even farmers.On March 1, 2025 (exactly four months after the tragedy), tens of thousands gathered in the southern city of Niš for a large commemorative protest.

Historic March 15th Protest

On March 15, the country saw its largest protest, reaching between 275,000 and 325,000 people nationwide.The protest marked a clear turn into a broader civil protest. Students had been joined by professors, teachers, taxi drivers, farmers, lawyers, and many other people.

Another (less pleasant) reason this protest was historical was that the government decided to use a millitary-grade sonic cannon ↗ to disperse the protesters in the middle of the peaceful 16 minute silence vigil. Sonic weapons like this can cause permanent physical and psychological damage, and are illegal to use in Serbia.While the government denies the claims ↗, over 500 people's reports of symptoms and video evidence of Serbian police loading the weapon the day before the protest](https://www.youtube.com/shorts/tYjZc712mGg) have provided evidence to prove otherwise.The government had also prepared a horde of masked hooligans ↗ to attack peaceful protestors that night.

April-May 2025: Hardline Government Response

In mid-April, a new government was formed under a little-known loyalist, Prime Minister Đuro Macut, after a prolonged delay in replacing Vučević. The cabinet reshuffle signaled a harder line: Vučić kept all key ministries under trusted alliess.Observers noted that the regime appeared to have “abandoned any pretense of dialogue” and was preparing to crack down on the protests rather than meet their demands.Indeed, as spring turned to summer, authorities increasingly sought to break up demonstrations with police action. Peaceful student sit-ins were met with eviction orders, and riot police presence intensified at protest sites.Vučić pointedly refused to call early parliamentary elections, a tool he had previously used to quell dissent, suggesting he would not concede to this movement’s central political demand.

Student Marches, Ultramarathon and Cycling

In April and May, student protesters organized a series of events to spread the message of Serbia's fight for democracy at a national and international level.

In Serbia, the students marched throughout the country ↗ to raise awareness of the protests in smaller towns and villages. State media has near 100% capture of rural areas of Serbia, and they do not report on the events.

Internationally, Serbian students ran a 2,000km ultramarathon to Brussels ↗ and then [cycled for 13 days to Strasbourg ↗](https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2025/04/16/after-cycling-to-strasbourg-serbian-students-meet-with-ep-and-coe-representatives/) to raise awareness among the EU public and institutions about the ongoing democratic backsliding and authoritarian drift under Vučić's regime.

Unfortunately, these events did not produce a response further beyond reporting that the goal of EU aligns with the student demands ↗, and that they are calling for a “thorough ↗ examination” of how corruption “led to the lowering of safety standards and contributed to [the Novi Sad canopy tragedy]”.The EU Parliament is still financially and officially supporting Vučić.

June–July 2025: Continued Unrest and Rising Tensions

Despite government pressure and general fatigue, the protests persisted into the summer, though there were ebbs and flows.By this time, hundreds of thousands of citizens had at some point participated in the anti-government rallies.Public opinion polls (reported in independent media) showed a significant decline in trust in the government, especially among young people.In response, Vučić’s SNS party organized loyalists to stage counter-protests and permanent encampments outside Parliament and the presidential building in Belgrade.

These encampments were meant to represent a counter-protest to student blockades of universities, made up of "students who want to study" (Ćaci).However, they were mostly made up of paid actors ↗.

Occasional scuffles and provocations were reported, but through most of mid-2025 the demonstrations remained largely peaceful.Protesters continued to press their key demands, and the government continued to dismiss those demands as illegitimate. Very little progress was made on the canopy collapse investigation ↗.

August 2025: Violent Clashes and Escalation

In early August, the situation dramatically escalated into violence – the worst unrest Serbia had seen in years.On August 13–14, as protesters attempted to march on SNS party offices in several cities, they were attacked by Vučić’s loyalists armed with sticks, rocks, and flares. Hooligans were recorded dragging protesters' beaten-up bodies around ↗ right next to the police, who did nothing to stop them. They even arrested a 12-year-old boy ↗ for participating in the protest.

Mobs of SNS supporters hurled firecrackers and salute fireworks ↗ into a crowd of protesters, right under their legs.Protesters fought back and ransacked the local SNS headquarters – shattering windows and tossing furniture out of the building. Police in full riot gear intervened with tear gas and batons.

Over the course of two nights, dozens of people were injured or arrested in the clashes. One startling incident saw an SNS loyalist at party headquarters in Belgrade fire a handgun ↗ into the air as rival groups fought, further heightening tensions.

A video ↗ surfaced on August 14th on Telegram, where the Serbian police were recorded posing in front of the arrested protesters, who were on their knees, looking at the wall. The atmosphere oozed an air of pride, which is particularly nauseating given the events that happened that night.

On the other hand, police officers who do not follow orders to attack the protestors lose their job ↗.

The August clashes marked a turning point: a largely peaceful protest movement was met by organized violence from the regime, suggesting the government’s intent to quell dissent through excessive force ↗.Yet, protests continued despite nine months of escalating state violence, making it one of Europe's most sustained challenges to authoritarian governance in recent history.

Bringing Power Back Into the Hands of the People

Throughout the nine-month period, the protests demonstrated remarkable innovations in democratic organizing.Students implemented plenum-based democracy within occupied faculties, making all decisions through hours-long discussions and majority-rule voting.The movement deliberately maintained decentralized leadership, using rotating spokespersons to prevent co-optation and violent coercion.Every day, citizens complete 16-minute silent protests from 11:52 AM to 12:07 PM, starting at the exact time of the railway collapse, and dedicating one minute per victim. This "Serbia, Stop" ("Zastani, Srbijo!") campaign spread to over 400 cities and towns, representing unprecedented geographic coverage for a Serbian protest movement.